Atomic shift operator

DIRAC allows the definition of an atomic shift operator .ASHIFT to be added to the Hamiltonian

where \(A\) is a sum over atomic types. For each atomic types a group \(I\) of orbitals may be specified with an associated shift parameter \(\varepsilon^A_I\). In this manual we shall see an example of its use.

Degeneracy-driven covalency: the case of CO

We consider carbon monoxide. We run a straightforward HF calculation using the input files CO.xyz

2

C 0.0000000000 0.0000000000 -0.6446681648

O 0.0000000000 0.0000000000 0.4836548352

and CO.inp

**DIRAC

.WAVE FUNCTION

.ANALYZE

**INTEGRALS

*READIN

.UNCONT

**WAVE FUNCTION

.SCF

*SCF

.CLOSED SHELL

14

**ANALYZE

.MULPOP

**MOLECULE

*BASIS

.DEFAULT

dyall.2zp

**END OF

using the command:

pam --inp=CO --mol=CO.xyz

Looking at the Mulliken population analysis in the output, we find for the lowest two occupied molecular orbitals:

* Electronic eigenvalue no. 1: -20.684805978278 (Occupation : f = 1.0000) m_j= 1/2

============================================================================================

* Gross populations greater than 0.01000

Gross Total | L A1 O s

--------------------------------------

alpha 0.9995 | 0.9992

beta 0.0005 | 0.0000

* Electronic eigenvalue no. 2: -11.369805624916 (Occupation : f = 1.0000) m_j= 1/2

============================================================================================

* Gross populations greater than 0.01000

Gross Total | L A1 C s

--------------------------------------

alpha 0.9997 | 0.9990

beta 0.0003 | 0.0000

We see that the first and second lowest occupied MO are \(O1s\) and \(C1s\), respectively, separated by a sizable energy of \(9.315\ E_h\).

Let us now see what happens if we bring the two atomic core orbitals into resonance. First we generate the carbon atomic orbitals, using input files C.inp

1

C 0.0000000000 0.0000000000 0.0000000000

and C.inp

**DIRAC

.WAVE FUNCTION

.ANALYZE

**GENERAL

.ACMOUT

**INTEGRALS

*READIN

.UNCONT

**WAVE FUNCTION

.SCF

*SCF

.CLOSED SHELL

4 0

.OPEN SHELL

1

2/0,6

**ANALYZE

.MULPOP

**MOLECULE

*BASIS

.DEFAULT

dyall.2zp

**END OF

and the command:

pam --inp=C --mol=C.xyz

The checkpoint file C_C.h5 contains the \(C_1\) coefficients:

h5dump -n C_C.h5 | grep C1

dataset /result/wavefunctions/scf/mobasis/eigenvalues_C1

dataset /result/wavefunctions/scf/mobasis/orbitals_C1

We next prepare the input file COshift.inp

**DIRAC

.WAVE FUNCTION

.ANALYZE

**HAMILTONIAN

.ASHIFT

C_C.h5

1

-9.315

1

AFOXXX

0

**INTEGRALS

*READIN

.UNCONT

**WAVE FUNCTION

.SCF

*SCF

.CLOSED SHELL

14

**ANALYZE

.MULPOP

**MOLECULE

*BASIS

.DEFAULT

dyall.2zp

**END OF

which notably defines an atomic shift operator for carbon which builds a projector from the \(C1s\) orbital and shifts it down by \(9.315\ E_h\). We run our calculation using the command:

pam --inp=COshift --mol=CO.xyz --put "ac.C=AFCXXX"

The Mulliken population analysis of the two lower orbitals now read:

* Electronic eigenvalue no. 1: -20.687541416409 (Occupation : f = 1.0000) m_j= 1/2

==========================================================================================

* Gross populations greater than 0.00010

Gross Total | L A1 C s L A1 O s A1 O _small B1 O _small B2 O _small

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

alpha 0.9996 | 0.4790 0.5203 0.0001 0.0000 0.0000

beta 0.0004 | 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0001 0.0001

* Electronic eigenvalue no. 2: -20.681935936276 (Occupation : f = 1.0000) m_j= 1/2

==========================================================================================

* Gross populations greater than 0.00010

Gross Total | L A1 C s L A1 O s A1 O _small B1 O _small B2 O _small

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

alpha 0.9996 | 0.5202 0.4790 0.0001 0.0000 0.0000

beta 0.0004 | 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0001 0.0001

and we indeed see that the two lowest molecular orbitals now are almost degenerate with concomitant strong mixing of the \(O1s\) and \(C1s\) orbitals.

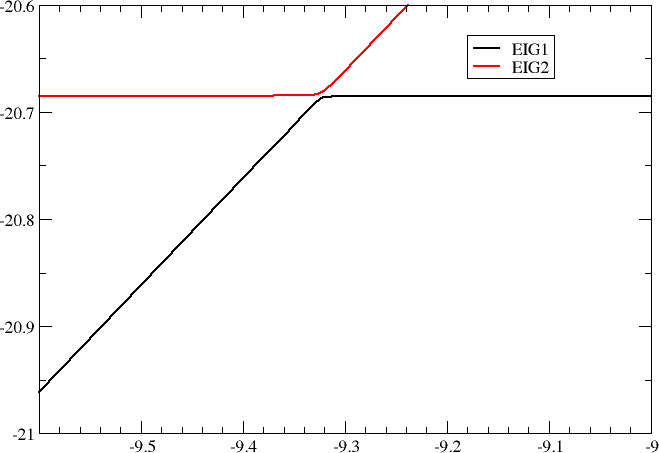

By scanning shift values in the resonance region we obtain the following plot of orbital energies of the two lowest occupied molecular orbitals

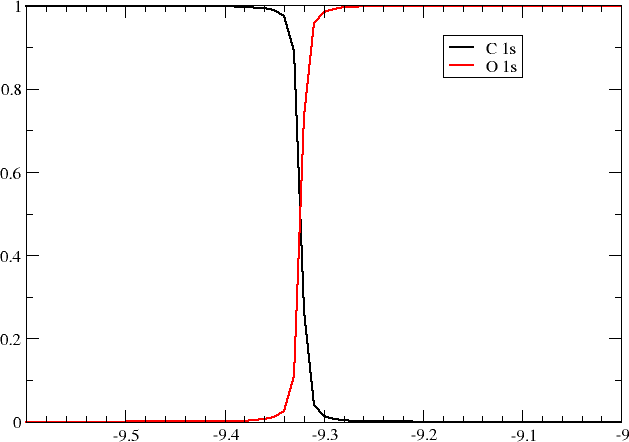

as well as the mixing of \(O1s\) and \(C1s\) orbitals in the LOMO.

At this point it may be useful to consider the diagonalization of a \(2\times2\) matrix

where eigenvalues are given by

We notably see that as we bring the two starting energies into resonance, that is \(\varepsilon_1=\varepsilon_2\), the difference \(\Delta\lambda\) becomes equal to the twice the interaction \(2|\delta|\). In this particular case \(2|\delta|=5.6\ mE_h\).

What can learn from this ? Neidig, Clark and Martin [Neidig_CoorChemRev2013] have introduced the concept of near-degeneracy driven covalency, where bonding interaction arises from near-degeneracy, even in the absence of overlap. In the above example we clearly see this mechanism at work: bringing the \(O1s\) and \(C1s\) orbitals into resonance causes strong orbital mixing. However, it would be absurd to call this bonding. The two atomic core orbitals can be disentangled by localization and we also note that their interaction is extremely weak.